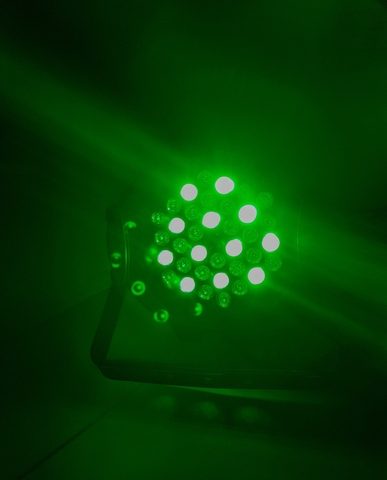

Green LED (light-emitting diodes) therapy may represent a novel, nondrug strategy for managing pain, with important implications for patients with fibromyalgia.

The study with the findings, titled “Long-lasting antinociceptive effects of green light in acute and chronic pain in rats,” was published in the journal Pain.

Chronic pain refers to pain that typically lasts for more than three months or past the time of normal tissue healing, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Chronic pain can be the result of an underlying medical disease or condition, injury, medical treatment, inflammation, or an unknown cause.

The prevalence of chronic pain varies, but according to CDC estimates, 14.6 percent of adults in the United States have current widespread or localized pain lasting at least three months.

Treatments for chronic pain are inadequate, and new options are needed. Nonpharmaceutical approaches are especially attractive with many potential advantages, including safety.

“Chronic pain is a serious issue afflicting millions of people of all ages,” Mohab Ibrahim, the study’s first author and assistant professor of anesthesiology and pharmacology at the University of Arizona (UA), said in a news release.

“Pain physicians are trained to manage chronic pain in several ways, including medication and interventional procedures in a multimodal approach,” he said. “Opioids, while having many benefits for managing pain, come with serious side effects. We need safer, effective and affordable approaches, used in conjunction with our current tools, to manage chronic pain.”

Light therapy is one nondrug approach that has been suggested as beneficial in certain medical conditions such as depression. But it had not been explored in the treatment of pain.

Ibrahim and colleagues examined the effects of green LED in rats with neuropathic pain.

One group of rats was exposed to green LED light (eight hours a day, wavelength 525 nm), while another group was exposed to room light and fitted with contact lenses that allowed the green spectrum wavelength to pass through.

Both groups were found to benefit from green LED exposure.

In comparison, another group of rats was fitted with opaque contact lenses which blocked the green light from entering their visual system. These rats did not benefit from green LED exposure.

Rats receiving green LED light showed significantly more tolerance for thermal and tactile stimulus compared to rats that were not exposed to green LED. There were no apparent side effects and the motor performance of the animals was not impaired by the green LED light.

“While the results of the green LED are still preliminary, it holds significant promise to manage some types of chronic pain,” Ibrahim said.

The beneficial effects lasted for four days after the final exposure.

“While the pain-relieving qualities of green LED are clear, exactly how it works remains a puzzle,” said Rajesh Khanna, UA associate professor of pharmacology and senior author of the study. “Early studies show that green light is increasing the levels of circulating endogenous opioids, which may explain the pain-relieving effects. Whether this will be observed in humans is not yet known and needs further work.”

The results indicate that green LED light can change the levels of substances that may inhibit pain and perhaps reduce inflammation of the nervous system.

The team is currently conducting a clinical trial using green LED therapy in people with fibromyalgia to see whether this type of light therapy can ease participants’ pain when used alone or combined with low-dose analgesics or physical therapy.